For the third and final iteration in this “The Hatred of Poetry” series, I want to tell you about something still so close that I find it difficult to know what it means or how to begin. It’s a little like revealing a middle school crush: you’ll be mocked for sure, but your heart will collapse in on itself if you don’t betray yourself and tell it to someone. So watch me betray and tell.

This book holds an indecent amount of joy for me, and a sharp grief that my dear partner in the enterprise, Tony Hoagland, is not here to share in its publication. The depth of the material had us barking ecstatically like seals, as if we were trafficking in rare jewels. Maybe we were.

A decade ago, Tony and I sat together outside a pub in the Welsh seaside town of Barmouth. After a week in the surrounding hills, we were enjoying the almost hallucinatory pleasure of a pint of Guinness whilst looking out over the Irish Sea. There was a plate of fish and chips we were picking at, and the sky was unrelentingly blue.

More swooning on my part. This book holds an indecent amount of joy for me as well. It came to me at an important time in my life, and I can’t tell anymore if it means so much to me because of that or if it really is just amazing. I don’t know the distinction matters. I just know that it moved my relationship to poetry unlike few things have before (save Poetry Unbound, but I’ll save that story for another piece).

Shaw tells the story of this collection’s conception even better here (and also reads a smattering of poems!):

So that was Martin Shaw in his forward to Cinderbiter: Celtic Poems. It came to me through some sort of leap-frogging recommendation (a friend introduced a friend introduced me to Snowy Tower last year as I was freaking out about teaching Parzival again, and then more Shaw followed). I was preparing for a week of backpacking near the coast, and I knew I needed to bring books that would help me to dive deeper and to dissolve myself into the landscape (a bone of teasing–contention between a friend and me: I’m the anti-Prospero, I don’t drown my books but drag them around with me everywhere I go). Thinking of Shaw’s argument that story needs reconsecration by retellings in the open air, perhaps around the glow of a fire in the wild dark, I grabbed copies of Courting the Wild Twin and Cinderbiter. I crammed them into my pack, anywhere they’d fit, and I devoured them on fir-topped mountains and wind-whipped winter beaches. It was a little too perfect. It was part of how I escaped death (or died and came back, I’m still figuring out which).

Enough preamble. Here’s the opening stanza from their version of the title piece:

The gray churn, the salted bruise, the green bridle; the seal-proud comb around Scotland's skulled coasts.

It’s a little silly to admit, but that couplet sold me on it. I knew I was in for it even while I had no idea what “it” would be. I knew I had found something that spoke to me and culled and called me in a way nothing I had read or was reading was doing.

Their philosophy on transforming these pieces is equally enthralling. Shaw’s point from the very beginning is that these are not translations from Gaelic languages: “It is a disservice to the vital work of translators to call these translations: they are not; they are versions.” As a storyteller, his approach to language is deliciously anti-scholastic or anti-pedantic in the sense that the language printed on the page is no more of an authoritative rendition than the language spoken live between the lyricist and their audience. It’s shockingly living language, and each piece has a pulse.

Another sample, this time from the piece that follows hard after “Cinderbiter”, “Deirdre Remembers a Scottish Glen”, by an unknown possibly fourteenth century Irish poet (hearing Shaw’s reading of it is unbelievable!):

Glen of my body's feeding: crested breast of loveliest wheat, glen of the thrusting lorn-horn cattle, firm among the trysting bees. ... Glen sentried with blue-eyed hawks, greenwood laced with sloe, apple, blackberry, tight-crammed amid ridge and pointed peaks. My glen of the star-tangled yews, where hares would lope in the easy dew. To remember is a ringing pain of brightness.

There’s a hint of Colin Meloy’s libidinousness in a lot of these poems (or maybe it’s the other way around). Perhaps that’s a Celtic trope. I’ve blushed reading some of these—lovely surprises of a wild sensuality mixed in with the pious and humble life of the hermitage. Every line is electrically alive. And somewhere in there, after Ben Lerner and Mary Oliver ever so lovingly boxed my ears and twisted my neck, I found a different way to think of and feel toward poetry, poetic traditions, and my place in this relationship to language that seems to have landed on my shoulders.

[aside: I always make a typographical error when typing “relationship”, my third finger is a little too eager, I overshoot to hit a second “o” instead of that second “i”, maybe making this into a truer word, “relationshop”, for any relation is a worksite, right?]

There are pieces here I need to go back to study better, and there are pieces here I need to never leave behind. I want to know them by heart and let them dance off my tongue like a lusty bard. “I make mead from this honey / and the good hazel-bush, / I make beer with scented herbs” (from “The Hermit’s Hut”, unknown Irish author, tenth century).

My God.

There is no quarrel here, no hour of strife. Bright song of the swan, be with me always, and the nimble wren in the hazel bough, and swarms of bees, and wild geese. The wind in the pines makes music sweeter than any harpist. I know where a patch of strawberries grows. How could I not think that God has sent these things to me?

I’d heard people like Paul Matthews talk about poetry as charm, as magic, as spell-making, but that always felt too twee. I never felt poetry was an incantation. I mean, I’ve been knocked on my ass by poems aplenty in the past couple years, but I’ve never felt that I or any other poet was conjuring something with words. But that keeps happening here: sparrows dart out of my mouth and into the branches of aspens, and the wind whips the river oaks and flush cottonwoods whenever I speak these aloud. It’s hella dope; you should try it.

Celtic poets rove the landscape: the byres, hillocks, and far-reaching horizons. Poets are scarecrows of words, fiends of divine encounter. They get thoroughly soaked. There’ll be a love affair somewhere along the way, an encounter with a spirit, maybe even a clash of swords. When they sit at table that evening, and the village crowds in, you can be sure they’ll have a story to tell.

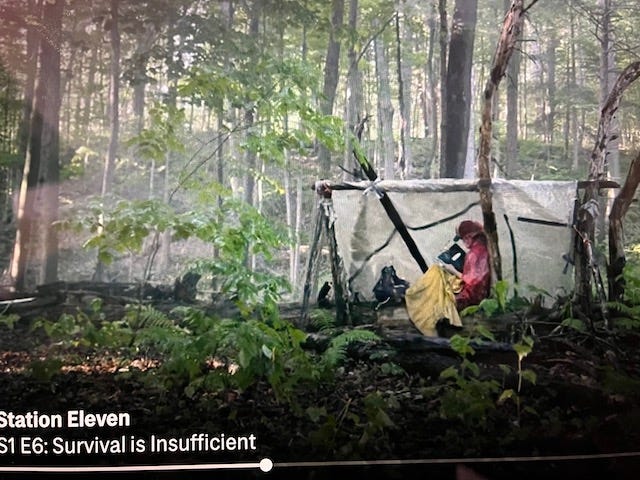

I can’t capture everything this collection has meant to me and to my evolving relationshop to poetry. I can barely articulate what I’m getting at here. I have obsessed over it like Kirsten obsesses over Station Eleven: sitting in the rain, under trees, losing myself in it.

The whole party ends with Tony Hoagland’s brief essays on the history of Celtic poetry and poetic tradition and how he and Martin Shaw went about this work of recasting and retelling these stories and poems in a druidic “kind of reanimation of old bones.” Hoagland’s explanation of the medieval schools run by the Irish bards to train young poets especially kidnapped my imagination in an unnervingly exciting way (see part 2 of this series for a discussion of, among other things, my (non)schooling in poetry).

The Irish bards, it seems, had schools in which young men, if they had an inclination, could study to become poets. These bardic training schools instructed the students in poetic technique, in the strengthening of memory, and in the cultivation of imagination. The training included annual examinations. Assigned a theme and a complex set of prosodic requirements, the young men would retire to special huts or cells, rooms entirely lacking in windows, lamps, or distraction. There, in the pitch-black, they would lie on their plain wooden beds, and slowly compose their poems, a text written and revised entirely in memory.

For a full night and a day, the poet would lie in the dark, thinking, muttering to himself, composing, revising, and repeating. On the second night, when the poem was due to be delivered in its entirety, an assistant would enter the room with a lamp; only then would the poem be committed to ink and paper. The students were then escorted to a common hall to recite their poem to the master-laureate. The process might take days; hardship was part of the making. According to other accounts of Gaelic composition in the Middle Ages, bards would lie on the ground with a heavy stone on their bellies for help with concentration.

Have heavy stones; Seeking hut. Will submit to tutelage.

Maybe breathing earth is opening our hearts and voices to speak it true.